From the beginning, Noor Inayat Khan longed to make a difference. At an early age, her father, Hazrat, a devout Sufi, instilled a deep sense of sacrifice, hope, and courage in her. In an effort to show Noor the responsibility he expected, he would often remind her that their family lineage could be traced all the way back to their ancestor, Tipu Sultan, once reigned over the Kingdom of India.

“You are royal,” he told Noor and her three siblings, “Nothing in this world can take that away. Do not be afraid to hold up your heads in any court in the world.”

So when World War II came knocking, Noor knew she had to help. After a successful round as a civil servant in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF,) she was recommended to the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.) for work as a wireless radio operator in 1942. Even though the risk of capture and death were likely in this type of work, she readily accepted the proposal. Her friend remembered that she had stars in her eyes when she shared the news with her.

It was the chance of a lifetime, but rife with danger from the start, as the average life expectancy for a wireless radio operator in Paris was just six weeks. It was, as the director of the SOE later pointed out, the “principle and most dangerous post in France.” Noor, however, lasted for a whopping three months in Paris. In the end, her radio work in the field not only enabled arms and explosives to be sent to the underground French resistance networks, but also aided 30 Allied Airmen who’d been shot down in enemy territory.

In later years, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, would admit that the S.O.E.’s work shortened the war on the European front by at least six months. Nearly 1 in 3 of the agency’s recruits in France died during their time in the field, and Noor would be no exception.

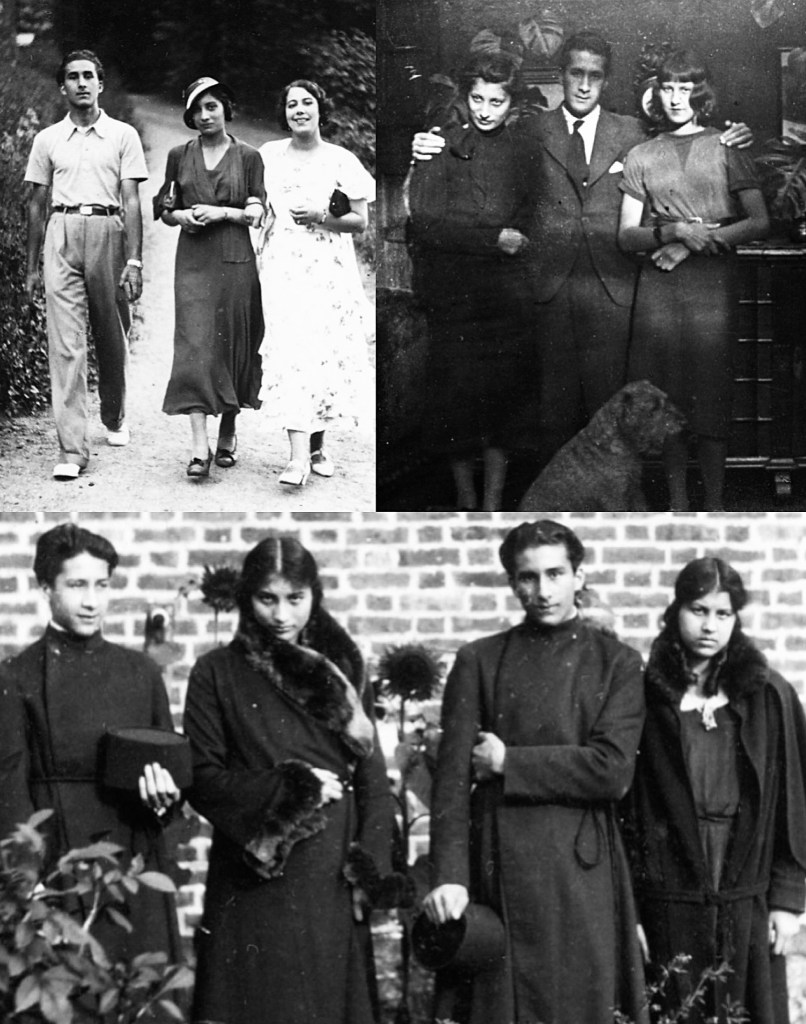

Right: Noor with her mother

BUILDING ROOTS

Born in Moscow just seven months prior to the start of World War I, Noor Inayat Khan was the first of four children born to Hazrat and Ora Ray Baker Khan on January 1st, 1914. Her parents had been newlyweds just a year before after meeting in the United States.

Not long after her birth, the family packed their belongings and moved to England, where they soon settled in London’s Notting Hill district. In the frugal years of World War I that followed, all of Noor’s three younger siblings were born. In an effort to support his growing family, Hazrat Khan spent most of his time on the road as a touring musician, often gifting his audiences with wisdom from the Sufi teachings he crafted his life by. Even with this income, though, money was tight, and Ora would often make simple meals that consisted of rice and bread to stretch their budget while ensuring they had enough food to get by each week.

After World War I ended in 1918, Noor and her family left England for what they hoped would be a more peaceful life in France, and settled in the picturesque town of Suresnes, just outside of Paris. They moved into a spacious house that stretched out over 3,500 square feet, alongside a beautiful estate that was situated high, on top of a hill near Mount Valerian, surrounded by gardens and nature. It was perfect for the growing family and her father, Hazrat, soon christened it, “Fazal Manzil,” (The House of Blessings).

But in 1927, tragedy struck after Noor’s father died suddenly of pneumonia while on a pilgrimage in his homeland of India. Completely distraught, her mother went into a deep stage of mourning that suddenly left Noor, as the eldest child, in charge of the rest of the family. But it was a role Noor would soon grow to love. She even gave weekly concerts for her siblings where she would play the piano and harp alongside recitations of her poetry.

Shortly after graduating from high school, she pursued her musical interests even further and enrolled in the Ecole de Musique in Paris to study, while taking psychology classes at Sorbonne University. During that time, she continued to write, and as her skills progressed she landed a job as a journalist at the local Le Figaro newspaper.

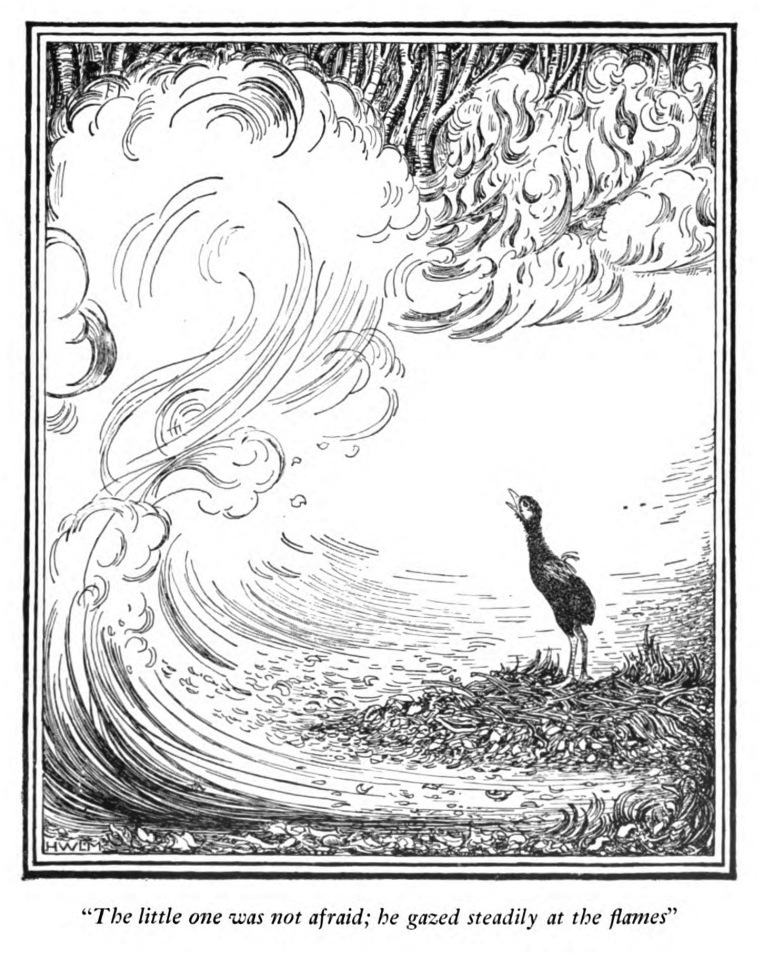

Meanwhile, outside of work, she crafted an exquisite composition of children’s tales, called Twenty Jakata Tales, which was later published in a book alongside illustrations by H.W. Le Mair.

World War II begins

As one decade ended and another began, any sense of normalcy Noor once had simply vanished. She soon found herself caught in the crosshairs of an ever-growing European conflict between Hitler and his quest to exterminate the Jews and their allies.

After his brazen invasion of Poland, the Nazi regime set out to conquer France. While the French, thought to have the greatest army in the world after World War I, did fight back, it didn’t do much good, as their military tactics hadn’t changed much since the onset of the war. The Germans, who had much more advanced military training and weapons, swooped in and overtook them in what seemed like a landslide. France’s then presiding Premiere, Paul Reynaud, likened the fall of their army to, “…walls of sand that a child puts up against waves on the seashore.”

As news of the German invasion spread across the country, terrified citizens, including Noor’s own family, packed up what little they could and fled in haste. Since not everyone had a car in those days, some were forced to walk, while others bicycled or rode in makeshift carriages with their horses down the streets.

Remembered as “The Mass Exodus,” the French Resistance leader, Marie-Madeline Fourcade, later recalled it with horrific detail. In her memoirs she wrote:

“People loaded furniture and knick-knacks onto vehicles of all kinds, as houses were cleared of their contents and passengers, furniture and objects alike took shelter under pyramids of mattresses,” she wrote. “ Dog owners killed their pets so they would not have to feed them. In this sad frenzy of departure people rescued whatever possessions they could save…. Weeping women pushed old people who had been squashed into prams.”

While Noor and her family were fortunate enough to have a car when The Mass Exodus began, they were still in a race against time. After a series of frenzied road trips and train rides, they were finally able to escape France by securing passage to England aboard a freighter ship named The Kasongo.

Life in England

After their ship docked in the county of Cornall, at Falmouth, they headed to Oxford, where other war refugees had recently settled. Once they found suitable housing, Noor, along with her sister and mother, signed up for volunteer work in the local area to help aid the war effort in any way they could. Her brother, Vilayat, headed to London, where he quickly joined the ranks of The Royal Air Force (RAF).

Noor first worked as an aide at a local maternity home, but didn’t find the work very fulfilling so she decided to enlist in the Women’s Auxillary Air Force (WAAF), in November of 1940, in part, no doubt, inspired by her brother, Vilayat. Since he had had complications with his initial RAF application, he advised Noor to register at the WAAF as a member of The Church of England and adopt a more traditional, English-sounding first name for her application. In an ode to her mother, Ora, Noor chose the name, “Nora.”

Noor becomes a spy

Once she finished the WAAF’s basic three week training program in Harrogate, England, she was assigned to a post in Edinburgh, Scotland where she learned the ins and outs of wireless radio operating.

For six months, Noor worked hard at mastering the art of transmitting Morse code. Eventually, her wireless radio operating skills gained so much traction that the WAAF selected her for a special post in Wiltshire to learn how to transmit specific symbols and instructions.

By the time of her yearly review with the WAAF, Noor was eager to prove her aptitude and skill set in wireless radio operating so she could start earning a living wage for her work. She had no idea that when she stood before the board they would inform her that they had already sent her credentials to a top secret intelligence agency that was looking for fresh recruits – The Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.).

She was contacted by the S.O.E. in November of 1942 for a private interview in London, at the Hotel Victoria, with Captain Selwyn Jepsen. During the interview, Noor immediately accepted Jepsen’s offer, and started training not long after. However, she soon ran into a problem as some of Noor’s instructors had doubts about her ability to succeed as a spy. In their reports, they noted that she was hesitant around using weapons, and often broke down in tears during practice interrogations.

But they were in great need of wireless radio operators and knew they couldn’t afford to lose Noor. Eventually, they disregarded their reservations and began making preparations to send her into the field.

In 1943 she was assigned to the S.O.E.’s French division, aptly called the, “F Section.” They needed her to help run their spy networks in Paris, as they were beginning to lose their wireless radio operators at an alarming speed. These networks helped run the underground resistance movement in France, and were the lifeblood of the organization.

Before her departure, she was given two code names. The first, “Madeline,” was the name she used in all of her wireless radio correspondence. The second, “Jeanne-Marie Reneir,” would be the general identity Noor assumed while working undercover as a spy in Paris.

At the time, the S.O.E. relied on Lysander planes to transport their agents, as they were able to land in more discrete areas, like grassy fields in the countryside, that were less patrolled by the Germans. The ones used by the S.O.E. often flew when there was a full moon, as it enabled the pilots to blend into the sky and see without ever having to use their own lights.

When Noor’s plane landed in the French countryside on June 17th, in 1943, she was met by Henri Déricourt, a corresponding agent already working in the Parisian PROSPER network where Noor was assigned. Unbeknownst to his peers at the time, Déricourt was secretly working as a double agent with the Germans. It was his work, no doubt, that led to the Gestapo’s arrest of all the other PROSPER agents within ten days of Noor’s arrival.

(Below) A type 3 mark II b2 wireless radio, similar to the one Noor used in Paris in 1943

When the S.O.E. heard of these arrests, they immediately messaged Noor to abandon her mission and take the next flight out to England, but she refused. Insisting she could rebuild the network on her own, Noor assumed the role of six wireless radio operators. She proved to be successful by being quick on her feet, and constantly evaded capture by spending no more than twenty minutes in one spot to send out her messages. As Noor quickly rose to the top of the Nazi’s Most Wanted List, she threw them off her trail numerous times by simply switching up the apartments she stayed in each night, while also inventing new disguises to alter her appearance.

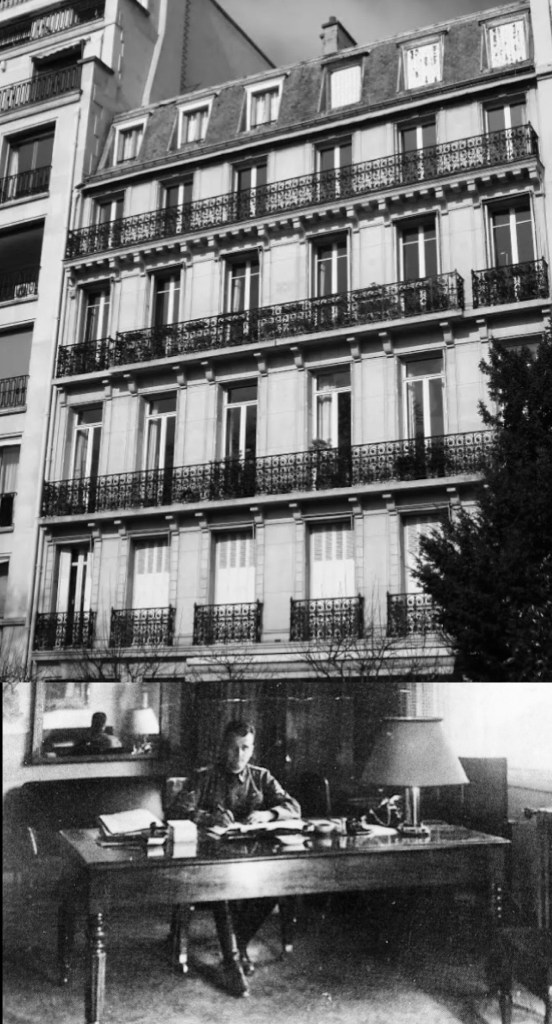

Noor was just days away from flying back home to England, in fact, when the Gestapo arrested her at her apartment in October of 1943. She had been betrayed by a woman in Noor’s social circle who was rumored to be jealous of a man she was dating, and given 100,000 francs as a reward. After her arrest she was sent for interrogation at Germany’s infamous Parisian headquarters at 84 Avenue Foch.

(Below) SS Officer, Hans Josef Kieffer, who interrogated Noor and other prisoners at 84 Avenue Foch

Everyone knew what went on behind closed doors at 84 Avenue Foch during the war, so much so that the Parisians called it , “The Street of Horrors,” since the screams of its captives eerily echoed throughout the area. The sixth floor of the building, near the roof, was where most of them were held and interrogated, including Noor.

She tried to escape her cell twice, but was captured each time. After the second escape attempt the Germans labeled her as a dangerous prisoner and a flight risk. For more secure arrangements, they transferred her to Germany’s Pforzheim prison, where her arms and legs were kept in metal shackles in a solitary cell for 24 hours a day.

The Gestapo would try to tempt her with better food and holding conditions for any information she could give them, but she never told them anything. They knew so little, in fact, that they thought her name was, “Nora Baker.” As punishment, they fed her with meager rations of a bland, watery soup filled with bits of potato peelings. Needless to say, it was a grim existence.

Then, in September of 1944, she was transferred with two other S.O.E. agents to The Dachau Concentration Camp in southern Germany, where her treatment was even more brutal. She was assaulted, beaten, and raped there by soldiers numerous times.

Not long after her arrival, Noor was ordered at dawn one morning to march with three other female prisoners to a nearby field in the woods, behind the prison’s crematorium. There, the commanding SS officers ordered each one to kneel and then systematically shot them all in the back of the head.

The final word rumored to have left Noor’s lips just before the Germans pulled the trigger was a defiant, “Liberté!”

She was only 30-years-old.

After the war ended in 1945, Noor became the first British Muslim war hero to be awarded the British George Cross. Later, she also received the French Croix de Guerre with a silver star. Both are regarded as the highest military awards in their respective countries. In 2012, a statue honoring her memory was placed in London’s Gordon Square Gardens.

To learn more, watch the movie, Enemy of the Reich: The Noor Inayat Khan Story, now streaming on Amazon Prime.

REFERENCES:

Basu, Shrabani. Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan. The History Press, 2006.

“BBC Timewatch – The Princess Spy (World War II). YouTube, uploaded by History Files, 1 May 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IObZOArCm6Y

Magida, Arthur J. Code Name Madeleine: A Sufi Spy in Nazi-Occupied Paris. W. W. Norton, 2020.

Mukherjee, Dipanjana. “Noor Inayat Khan: Britain’s First Muslim War Heroine.”STSTW Media. https://www.ststworld.com/noor-inayat-khan/

“Noor Inayat Khan: Why Was the British Spy Such an Unlikely War Hero?”, History Extra.

https://www.historyextra.com/period/second-world-war/noor-inayat-khan-secret-agent-spy-life-death/

Tsang, Amie. “Overlooked No More: Noor Inayat Khan, Indian Princess and British Spy.”The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/28/obituaries/noor-inayat-khan-overlooked.html